For me, there's something more than a little worrying about the current growth in Aquaculture, i.e. the intensive rearing of aquatic animals in closed pens for human consumption. Didn't some bright spark in the fifties have the same idea regarding egg production? The overwhelming majority of articles I see in the media seem to report aquaculture as a good thing, the way forward, the solution to the collapsing wild fisheries. Packs of Haddock and Prawns in my supermarket proudly proclaim their 'sustainably farmed' origins while 'wild' caught fish, responsibly caught, seem to be increasingly rare.

So . . . is it okay now to continue to deplete our resources of large wild fish in the knowledge that we can farm them instead?

Beware. With industrial techniques come industrial processes. Some very potent drugs and chemicals are used to keep the thousands of fish crammed in the pens alive, free from disease and the cages clean. These chemicals promote unnatural growth, stimulate reproduction cycles, deter sea-lice and even colour the flesh of the rapidly grown fish to a more natural hue. Inevitably the drugs, pesticides, bleaches and concentrated fish waste escape into the surrounding marine environment through the netted walls and floors of the pens causing enormous harm to the natural ecosystems in the local area. The mature fish from these farms look entirely normal.

At the end of this 'responsible' process we eat the fish!

Some farms are undoubtedly more environmentally conscientious than others, but without more stringent environmental controls in place how can we have confidence in what we're eating. It may well be, perhaps, that large scale aquaculture will prove to be beneficial and ultimately reduce pressure on wild stocks but surely we cannot allow the industry to develop unchecked and too late discover the cost.

Monday, 24 August 2009

Tuesday, 18 August 2009

The very air

It's not only the much-maligned seafood lovers of Japan and East Asia that drive the increasingly desperate fishing industries to chase down their prey in newer, more imaginative ways. Consumers from the western world too must, of course, bear a significant responsibility for the demise of once abundant species from Atlantic, Icelandic and Baltic fishing grounds. There is, after all, only one ocean and we are eating our way through it - literally - from top to bottom, and it's killing us . . . un-noticeably slowly, but certainly surely.

Cod, Monkfish, Halibut and Plaice, to name but a few of the most serious cases, have been trawled from the seas around our island in unsustainable numbers for too many years with too little complaint, perhaps to the point of no return. Instead, much of the fish you'll find in your local chippy or supermarket is now taken from Icelandic or Baltic waters, so-called sustainably managed fisheries. But for how long and who's doing the managing? Where will we find our favourite fillet when we've exhausted these new supplies? Larger boats, with inevitable short-sightedness, will trawl smaller waters for lesser fish of fewer species. Will our governments continue to subsidise their livelihoods when we're paying £15 for a portion of cod and chips? We're taxing our own demise.

Many supermarkets offer trendier options such as Swordfish, Snapper and Marlin, vitally important predator species that are facing imminent virtual extinction in large areas of the world. Yet, there they lay, sliced up on beds of clean white ice behind the glass counter next to the expanding selections of squid and jellyfish (get used to it!). If prime cuts of Panda belly were laid out waiting for the frying pan, shoppers would be sidestepping placarded protesters chaining themselves to the doors and leafleting every windscreen wiper.

The vital piece of information that many of us are ignoring is that the imminent removal of each species is about more than just not having them served up in a nice beer batter with some chunky chips . . . it's about the very air we breathe. The removal of predator fish and near extinction of primary food fish ultimately and irretrievably leads to acidifying oceans and global warming.

If you give even the smallest of damns about your planet or just your fish, ask where it came from. While there's a market, unsustainable and unregulated industrial fishing methods will continue, somewhere, somehow. Check the label. Take an interest. Ask where the fish were caught, and just as importantly HOW they were caught. It matters! It's a simple measure that everybody can take at no cost and will have a positive impact on our ecosystem.

Labels such as 'line caught' may conjure up images of woolly-sweatered boat anglers with a rod and a bucket of worms but in truth usually means 'long-lining', an incredibly indiscriminate method of fishing which takes thousands of tonnes of illegal bycatch. Sustainable means 'pole-caught', 'seine-netted' or 'midwater trawled'. UN-sustainable means 'line caught', 'dredged' or, perhaps worst of all, 'bottom trawled' a remarkably efficient method of mass destruction, turning sea beds into muddy bottomed wastelands, violently devastating every iota of life in the path of the trawl beam.

Jelly fish continue to thrive.

Cod, Monkfish, Halibut and Plaice, to name but a few of the most serious cases, have been trawled from the seas around our island in unsustainable numbers for too many years with too little complaint, perhaps to the point of no return. Instead, much of the fish you'll find in your local chippy or supermarket is now taken from Icelandic or Baltic waters, so-called sustainably managed fisheries. But for how long and who's doing the managing? Where will we find our favourite fillet when we've exhausted these new supplies? Larger boats, with inevitable short-sightedness, will trawl smaller waters for lesser fish of fewer species. Will our governments continue to subsidise their livelihoods when we're paying £15 for a portion of cod and chips? We're taxing our own demise.

Many supermarkets offer trendier options such as Swordfish, Snapper and Marlin, vitally important predator species that are facing imminent virtual extinction in large areas of the world. Yet, there they lay, sliced up on beds of clean white ice behind the glass counter next to the expanding selections of squid and jellyfish (get used to it!). If prime cuts of Panda belly were laid out waiting for the frying pan, shoppers would be sidestepping placarded protesters chaining themselves to the doors and leafleting every windscreen wiper.

The vital piece of information that many of us are ignoring is that the imminent removal of each species is about more than just not having them served up in a nice beer batter with some chunky chips . . . it's about the very air we breathe. The removal of predator fish and near extinction of primary food fish ultimately and irretrievably leads to acidifying oceans and global warming.

If you give even the smallest of damns about your planet or just your fish, ask where it came from. While there's a market, unsustainable and unregulated industrial fishing methods will continue, somewhere, somehow. Check the label. Take an interest. Ask where the fish were caught, and just as importantly HOW they were caught. It matters! It's a simple measure that everybody can take at no cost and will have a positive impact on our ecosystem.

Labels such as 'line caught' may conjure up images of woolly-sweatered boat anglers with a rod and a bucket of worms but in truth usually means 'long-lining', an incredibly indiscriminate method of fishing which takes thousands of tonnes of illegal bycatch. Sustainable means 'pole-caught', 'seine-netted' or 'midwater trawled'. UN-sustainable means 'line caught', 'dredged' or, perhaps worst of all, 'bottom trawled' a remarkably efficient method of mass destruction, turning sea beds into muddy bottomed wastelands, violently devastating every iota of life in the path of the trawl beam.

Jelly fish continue to thrive.

Monday, 17 August 2009

Find what you love

The following is a quote from a talk by Steve Jobs CEO of Apple Computer and of Pixar Animation Studios, delivered on June 12, 2005. It's a great story, and one which I can relate to. It's about not trying to look too far ahead, just go with what you love and the future will take care of itself, often for the better.

[quote]

I dropped out of Reed College after the first 6 months, but then stayed around as a drop-in for another 18 months or so before I really quit. So why did I drop out?

It started before I was born. My biological mother was a young, unwed college graduate student, and she decided to put me up for adoption. She felt very strongly that I should be adopted by college graduates, so everything was all set for me to be adopted at birth by a lawyer and his wife. Except that when I popped out they decided at the last minute that they really wanted a girl. So my parents, who were on a waiting list, got a call in the middle of the night asking: "We have an unexpected baby boy; do you want him?" They said: "Of course." My biological mother later found out that my mother had never graduated from college and that my father had never graduated from high school. She refused to sign the final adoption papers. She only relented a few months later when my parents promised that I would someday go to college.

And 17 years later I did go to college. But I naively chose a college that was almost as expensive as Stanford, and all of my working-class parents' savings were being spent on my college tuition. After six months, I couldn't see the value in it. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life and no idea how college was going to help me figure it out. And here I was spending all of the money my parents had saved their entire life. So I decided to drop out and trust that it would all work out OK. It was pretty scary at the time, but looking back it was one of the best decisions I ever made. The minute I dropped out I could stop taking the required classes that didn't interest me, and begin dropping in on the ones that looked interesting.

It wasn't all romantic. I didn't have a dorm room, so I slept on the floor in friends' rooms, I returned coke bottles for the 5¢ deposits to buy food with, and I would walk the 7 miles across town every Sunday night to get one good meal a week at the Hare Krishna temple. I loved it. And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on. Let me give you one example:

Reed College at that time offered perhaps the best calligraphy instruction in the country. Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn't have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can't capture, and I found it fascinating.

None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, its likely that no personal computer would have them. If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do. Of course it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backwards ten years later.

Again, you can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life.

(Source: Steve Jobs)

[quote]

I dropped out of Reed College after the first 6 months, but then stayed around as a drop-in for another 18 months or so before I really quit. So why did I drop out?

It started before I was born. My biological mother was a young, unwed college graduate student, and she decided to put me up for adoption. She felt very strongly that I should be adopted by college graduates, so everything was all set for me to be adopted at birth by a lawyer and his wife. Except that when I popped out they decided at the last minute that they really wanted a girl. So my parents, who were on a waiting list, got a call in the middle of the night asking: "We have an unexpected baby boy; do you want him?" They said: "Of course." My biological mother later found out that my mother had never graduated from college and that my father had never graduated from high school. She refused to sign the final adoption papers. She only relented a few months later when my parents promised that I would someday go to college.

And 17 years later I did go to college. But I naively chose a college that was almost as expensive as Stanford, and all of my working-class parents' savings were being spent on my college tuition. After six months, I couldn't see the value in it. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life and no idea how college was going to help me figure it out. And here I was spending all of the money my parents had saved their entire life. So I decided to drop out and trust that it would all work out OK. It was pretty scary at the time, but looking back it was one of the best decisions I ever made. The minute I dropped out I could stop taking the required classes that didn't interest me, and begin dropping in on the ones that looked interesting.

It wasn't all romantic. I didn't have a dorm room, so I slept on the floor in friends' rooms, I returned coke bottles for the 5¢ deposits to buy food with, and I would walk the 7 miles across town every Sunday night to get one good meal a week at the Hare Krishna temple. I loved it. And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on. Let me give you one example:

Reed College at that time offered perhaps the best calligraphy instruction in the country. Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn't have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can't capture, and I found it fascinating.

None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, its likely that no personal computer would have them. If I had never dropped out, I would have never dropped in on this calligraphy class, and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do. Of course it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backwards ten years later.

Again, you can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life.

(Source: Steve Jobs)

Wednesday, 12 August 2009

Shifting the baselines

Given the apparent inevitability of the earth getting warmer, at what point does it become too late to avoid the buffers? Have the horses long since since fled the barn? Is it true to say that whatever steps we take to change our behaviour, the path can never bring about the reversal of 100 years of industrial disease? So why try?

We can, maybe, alter our habits and slowly lessen the speed of the decline, but this will never be a quick process or a complete one. How many decades will pass before we start to regain the ground we've lost? Many scientists agree that an irreversible tipping point may be only 10-15 years ahead of us! Let's not kid ourselves that serious and practical consideration for our environment will become the No. 1 priority anytime soon for a society built on consumption and greed.

We can, maybe, alter our habits and slowly lessen the speed of the decline, but this will never be a quick process or a complete one. How many decades will pass before we start to regain the ground we've lost? Many scientists agree that an irreversible tipping point may be only 10-15 years ahead of us! Let's not kid ourselves that serious and practical consideration for our environment will become the No. 1 priority anytime soon for a society built on consumption and greed.

A familiar problem with our perception is referred to as 'shifting baselines' or to put it another way, people don't miss what they never had to appreciate in the first place. Every generation bases its life-view on what exists in their moment, their time. The oceans, the environment and the wildlife differ only slightly from our childhood, but the cumulative damage from generation after generation is almost beyond repair and in some cases already past fixing.

Fifty years from now, scuba divers and naturalists will still seek out what's beautiful in the oceans, and just as now, fight to save what they have. They'll spend some time trying to appreciate what's been lost for ever but will not, of course, be able to bring it back.

So do we continue to shift our baselines and move happily forward, each generation accepting what it has as the norm? . . . . Of course not. We have to round up the horses, recover what our ancestors misplaced. The responsibility of those 'in the moment' is to freeze the baselines of our generation and try to pass them down unaltered so others may have what we have. Perhaps future generations will no longer look back and lament the greed and the mistakes of the past, but instead be grateful that our generation was the first one to understand the problem and begin to apply a solution, however imperfect.

We cannot bring back extinct fauna and flora from pre-industrial days and perhaps we cannot immediately stop the temperature-raising carbon build up, but just because we cannot see the end of the line, doesn't mean that we cannot begin applying the brakes with greater urgency. We can't see precisely what outcomes will result and what real impact we can make, but even a little positive change is better than lazy indifference. Perhaps we'll see no change at all in our lifetime, but we have to look further than ourselves and do what we can regardless.

The buffers lie ahead somewhere, and we need to tie down what we have.

Sunday, 9 August 2009

Adventurise

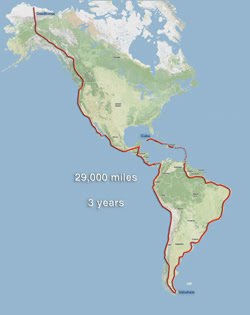

Adventure racing is fun. Tough, muddy, fun and a guilt-free way of consuming 2000 calories of fried food in a single sitting afterwards. As a way of beginning to raise awareness about my cycling expedition around the americas' I spend odd weekends competing in outdoor events where I can chat to like-minded folk and get some feedback about my plans for 2011. Triathlons, cycling sportives, MTB trails, half-marathons etc. are all enjoyable accomplishments but my favourite is adventure racing. This is fantastic and addictive way of exploring large amounts of beautiful English coastline, deep forest, rocky foreshore, serene lakes and muddy trails. Teams and individuals turn up suitably prepared for 4, 8 or even 24 hours of full-on charging around the designated local environment using various modes of travel including, but not limited to: running, mountain biking, kayaking, climbing, zip wires and anything else a devious course setter can accommodate. About 5 minutes before the staggered starts (to stop people following the guy in front!) competitors receive a map which give them fairly precise locations to dozens of electronic checkpoints with differing points values. The rest is simple. Get through as many checkpoints as possible, using the relevant mode of travel, collect the points and return to the finish before the time limit expires, after which penalty points can be incurred at a rate which can render the whole day's exertions as pointless, literally. Checkpoints are usually reasonably well hidden in beach front caves, undersides of rickety wooden bridges, in the middle of a muddy bog or half-way up a tree. You'll return exhausted, probably muddy, maybe wet and definitely hungry. The most proficient competitors will expertly plan and time their route around the area ensuring they reach the finish line with perhaps a minute remaining. As for myself and my teammate, our timing is sometimes a bit out, and we arrive home with 20 or 30 minutes remaining, not really enough to venture back out and find some more points and usually too knackered anyway. However, this methods ensures we tuck in before the BBQ runs out of cheeseburgers. All the winners get is a medal.

Wednesday, 5 August 2009

cyclisto imbecilios

So . . . there I am, merrily pedalling my down Chiswick high street giving a cheery wave to the polite bus driver as he nudges the front wheel of his vehicle ahead of me and shepherds me gently onto the pavement. I ever so gently remonstrate with him, but his hand gestures suggest he may not be willing to discuss the matter over a drink after work. Carrying on my way, I'm pondering on the meaning of 'imbecile' when I'm confronted with the real reason why London cyclists are sometimes regarded so lowly. I'm overtaken by your typical bad news bike courier, one geared, minimalist, grubby chic machine ridden by a grubby chic imbecile. I fail to understand exactly how he's unable to see the half a dozen people walking legitimately across the zebra crossing 4 yards in front of him. Not even slowing, he careers at terminal velocity through a 12 inch gap between the 6-year-old and the old lady, offering loud advice to both of them on the danger of being on the road at this time of day. Every cyclist in London bears the brunt of the antagonism created by this idiocy every day. The bad feeling created by the few is shared out equally among the many. If my bus driver friend actually managed to swat one of these morons, I'd happily buy him a drink.

Monday, 3 August 2009

Fishy tales

When I first began taking an interest in the sea, it was as an angler wholly ignorant of issues of species populations, biomass and food chains. There was something wonderfully raw and wild about the sea, and something mysterious about its depths. I'd read reports and seen pictures of 200lb marlin and tuna being hauled up onto the quayside and readily bought into the vision of men as proud hunters battling the elements and their prey and emerging victorious. The problem was, however, that when I went fishing there was no prey taking my hook. I persevered and mastered the craft, researched the baits and feeding habits of my chosen target. I listened to the boat captains and the old sea dogs telling me where great fish were to be found. It took some time to realise that generally these guys were telling me about the days of their youth, when they could pluck the cod out of the sea with every cast and every trip would be plentiful. Even younger skippers wouldn't seemingly not get dishearted with the declining numbers, they'd justput it down to the weather, try another day, search another patch, change the baits. They never appeared to want to admit the real problem, that harvesting requires seeding, farmers leave their fields fallow in order for them to recover nutrients. Not so the fishing industry. It is, of course, essential to their job security to talk up the prospects of big catches to their clients. When I began fishing, my biggest enjoyment was to see the fish close up and then watch them swim away. Since this was my goal, I later found a much better way to achieve this with Scuba diving, and stopped fishing. Many skippers see the benefits of catering to divers and have turned away from fishing. I'm amazed that local authorities cannot see the economic benefits of the dive industry replacing an unsustainable fishing industry along our coasts. Why can't we sink more artificial reefs, invest in an industry which has a future. I spend a great deal more money diving that I ever did fishing, it's a boom industry and a sustainable one!

This will be my mission statement, and pretty much sums up what I'll be doing. Hopefully it will remain true up to and through the journey. It's totally impossible at this stage to know what curve balls will get thrown my way over the next two years prior to leaving. But this gives me a 'baseline' which I can publicise and begin raising some charity funds. If things change then I'll roll with them as they do.

Sunday, 2 August 2009

links in a people chain

If all life on land were to vanish tomorrow, the creatures in the oceans would replenish and thrive. But if the life in the oceans were to perish then we would perish with them and this is the course we currently hold. We're all capable of understanding this, yet many of us choose to turn a blind eye, to declare what's beneath the waves as out of sight, out of mind. How long do we ignore what's happening? How devoid of life do the seas have to be before we realise that not having fish to eat will be the least of our problems?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)